I’ll let you in on a secret

about how one should pray the

Minchah prayer. . .

. . . you’re just lending a helping hand to the sinking day.

It’s a heavy responsibility.

You take a created day

and you slip it

into the archive of life,

where all our lived-out days are

lying together.

The day is departing with a quiet kiss.

It lies open at your feet

while you stand saying the blessings. You can’t create it yourself, but you can lead the day to its end and see clearly the smile of its going down. See how whole it all is,

not diminished for a second,

how you age with the days

that keep dawning,

how you bring your lived-out day

as a gift to eternity.

(excerpt from “Davennen Mincha”, a Yiddish poem by Jacob Glatstein)

If you watch carefully, you will notice a subtle but visceral shift in your consciousness, in that twilight between day and night, which is called ‘mincha’ in the daily rhythm of Jewish prayer. It is that almost imperceptible moment when you begin to absorb the day’s experiences and insert them into your personal memory file, to go from living in the moment to processing the day. As the poet Jacob Glatstein says, “you take a created day and you slip it into the archive of life . . .” Perhaps this is especially noticeable when you’ve had a day of particular significance, or, in our case, a whole season.

This is how I felt at dinner earlier this week, outside one of the local ‘fast-casual’ places, eating a pita sandwich, seated at a simple counter facing the street. I looked around at the nearby establishments, just slightly less tourist-oriented than those fancier ones around the corner, the store-front post office, appointments preferred for service, directly across the street, flanked by the barber shop and the gourmet cheese and olive shop. Cars and motorcycles whizzed by on the narrow street and pedestrians passed by, sometimes stopping to peek into the sandwich shop, sometimes catching my eye, other times busy with their own thoughts or conversations. The small bakery בונג׳ור (“Bonjour”) where we’ve bought challah for Shabbat, the אמריקן פיצה (“American Pizza”) which we’ve studiously avoided, the housewares store with everything from candy and flowers to fancy doormats, all busy with patrons in the final business hour of the day. Even the town “drunk”, really a mentally disabled person, whose social filters do not prohibit him from sitting at an outdoor table calling out an incoherent set of verses, only to be gently shooed away by a shopkeeper. The synagogue down the street, just beyond my sightlines, with its lovely building and women’s balcony, which I visited only as a tourist, and which hosted a raucous and joyous bar mitzvah celebration on Monday morning. Our vision for this sabbatical was to really get to know a place, to become a part of it, and to absorb it into ourselves, and in some small ways, we’ve succeeded in that. The locals no longer insist on answering us in English and we’ve learned some of the unspoken social cues, both explicit and implicit, of residents. The ubiquitous dust of Zichron Yaakov seems now forever under our skin. Last week, we finally took an official tour of the town with an acquaintance who is a seasoned guide, helping us to put more of the historical puzzle pieces into place. Along the way, we learned more about one of the founding couples, Moshe and Yocheved Hershkovitz, originally from Romania, who arrived here in 1882 and whose descendants still live in their family home on the central street. The current elder who lives there was unimpressed when I suggested that we might be related, since my paternal grandfather, Isidore Hershkovitz, z’l, also from Romania, landed with his family in New York instead of Haifa as a child. But who knows?

This coming Sunday, we’ll have the honor and pleasure of a Zoom conversation with the author and translator Hillel Halkin, whose writing has been such an inspiration to me and so many others. Halkin made aliyah from the States in 1970, landing in Zichron Yaakov when it was truly a small town. He has produced many important works, mostly non-fiction, and one about the town itself which includes the provocative disclaimer on the title page, “this is a work of fiction.” Perhaps this was the result of sound legal advice, or perhaps he, like us, has simply experienced this place as having its own midrashic reality, superimposed over the concrete one.

Several years ago, I was blessed to join a Shabbat afternoon shiyur (learning session) with the great R. Arthur Green. He shared that day about the word daven, the Yiddish word we take to mean to pray or to lead prayer. Surprisingly, it has an untraceable etymology, neither Hebrew nor German in origin. Providing a caveat that this explanation was undocumented, he went on to say that he’d heard that the word daven was actually derived from a Lithuanian expression meaning, “gift”. This was, he said, because somewhere in Jewish history, Jewish shopkeepers needed to explain to their gentile fellow merchants why they needed to briefly close up shop every afternoon, to say their afternoon prayers, called mincha in Hebrew, which means ‘offering’ or gift

So, Glatstein’s poem, “Davenen Mincha” is a doubled-over gift, a gift-offering, which is exactly what this sabbatical has been for us. It has been a gift of singular meaning, beauty, challenge, growth and longing for us and, likewise, one that we also hope to give back in our lives in many ways, through our work, our relationships with family and friends, and through continuing to navigate that impossible path between profound love for and connection with this land and the concern that always accompanies love.

And, finally, like the Shabbat mincha prayer service with its purposeful mix of Sabbath and weekday melodies, which acknowledge the palatial quality of Sabbath time and the irrepressible pull forward into the workweek, we are looking forward to concluding our time away and returning home, to beginning a new professional chapter, to resuming life in our native language and culture, to reconnecting with loved ones in the same time zone, and, just as we end Shabbat by anticipating the next one, to planning our next visit to Israel.

Post-script: Last night was a terrorist shooting, this time in Dizengoff center in Tel Aviv, another in a sudden eruption of multiple surprise attacks against innocent civilians. Everyone is somber and tense as we enter our final Shabbat before Pesach. There’s little else to say but to wish solace for the families of the victims and the hope that somehow this violence will end.

It is late Tuesday night and Jonathan and I are just back from an intense three days, two in Jerusalem and one in Tel Aviv. Heads up: this will be a long post, no pressure to finish in one sitting or at all.

Sometimes the practical reality of logistics determines when and where you’re going and what you’re doing. So it was this week, as we cobbled together a series of meetings and connections with various people on our “list”. In the end it was a demanding and rewarding chance to get out of our Zichron bubble, lovely though it is, and get a sense of some of the overwhelming challenges facing this tiny spot on the globe.

Just for background, we spent last Shabbat busily procuring and serving the kiddush at Kehilat Veahavta, our “oneg duty” offered as a gesture of thanks to the community that has so warmly welcomed us during our time here. Our kiddush included some beautiful fruit platters prepared by the staff at the small grocery near our apartment. I mention this here because these platters inspired many comments of admiration and appreciation by synagogue members, who enjoyed the handiwork of the Arab grocery staff who have been so gracious towards us. When we went to inquire about these platters and order them for pickup on Friday, the grocery manager responded as any good Jewish balabusta (hostess with the mostest), fruit for kiddush? No problem. How many people? You could almost forget there was a hyper-tense combustible situation between Arabs and Jews in other parts of this country. We picked up the trays and other items and brought them to the synagogue, then rushed home to meet Idan and his partner Pe’er for lunch.

And then, as plans took shape for the series of visits we wanted and needed to make, we packed our backpacks and got on the train from Binyamina to Jerusalem early Sunday morning. I had been nursing some really uncomfortable abdominal/rib pain and wondered how I’d manage all that we had planned, while also wondering what horrible diagnosis awaited me. (I am relieved and happy to report it was resolved and turned out to be nothing more than some musculoskeletal strain which did finally relax.) Even from the train ride itself, we were aware of how cloistered our time in Zichron Yaakov has been. The train station on Sunday morning was bustling with people returning to their workweek after Shabbat, adults en route to work, and many soldiers returning to their posts. I had not seen so many soldiers on this trip until that morning at the train station. It is still a jarring sight to see a young adult in uniform carrying an Uzi. A phalanx of thoughts jockey for attention in my busy mind: it is sad that young people have to serve in the military – a constant reminder about the as yet still hostile neighborhood that is the Middle East, it is admirable that these young adults take their responsibility seriously despite their age and relative innocence, it is laudable that this system of mandatory service creates a culture of investment and leadership, at least for some. And it would be disingenuous to omit the real trauma at least some of these young adults experience as a result of their service. A growing number are refusing to serve and/or simply finding ways around it, but the vast majority still do. For some it is a unique opportunity for educational, professional and personal advancement. And it is one of the reasons that Israelis hold on to their loved ones extra tightly. While most soldiers come through intact and many with advanced training, skills and achievement, not to mention lifelong friendships, professional connections, and the rewards of public service, there is always the real possibility that they won’t come home at all.

On the train ride, I sat next to an Arab Israeli family of four, a mom, a dad and a young son and daughter, all dressed in modern clothing, dragging suitcases and backpacks. At one point, the children were given activity books to work on and a pack of magic markers, their parents gently guiding them from one page to the next, holding them in their laps. The nearby soldiers didn’t make me uncomfortable, but I had to wonder how it felt to be a mom with a young child in my lap, and a large and deadly weapon very nearby, held by a soldier of an historically adversarial government. I did my best to smile (through my mask) at the boy and express my admiration for his excellent coloring book skills.

We arrived in a Jerusalem train station busy with people coming and going and found our way to the nearby Machane Yehudah to find a quick bite on our way to our first connection, the child of a family friend who graciously offered to show us around their home in east Jerusalem. Our host insisted on meeting us at our hotel and ferrying me to the nearest medical clinic to get my pain situation examined, then retrieving us to go on with our afternoon plans. (The experience at the clinic was smooth, well-organized, effective. I was heartened to see both Jewish- and Arab-Israeli patients in the waiting room, including one little boy who was clearly in distress, and ultimately calmed only by the Jewish doctor attending him. I was tested, given a strong pain-killer, reassured that I would be fine and sent to the receptionist to pay my bill.) We stopped for a beautiful lookout over the city and began an hours-long conversation about the political situation and then made our way to our host’s apartment in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah. You will likely recognize the name of this area which has been in the news on and off for the last few years especially, as local residents and liberal Jewish activists protested the eviction of several Arab families by Israeli authorities. Our host also showed where a number of Jewish “microsettlements” have begun to appear. These are small areas of maybe 2-3 homes, illegally and unsafely built by religious Jewish Israelis often illegitimately claiming rightful access to this land, fully expressing my own bias here. On our walk through the area, we had our host’s beautiful Goldendoodle puppy with us, happily ambling along, the subject of both abject fear by Arabs who feel stereotypically uncomfortable around dogs as well as fascinated admiration and even requests to purchase the dog for breeding. Our host chatted them up when they offered a price, refusing these overtures and also joking with them when they asked, “why do you have a sheep?” Not a sheep, not for sale!

Our walk through the area gave a real life vignette of just how diminished civic infrastructure is here compared with west Jerusalem, just meters away. In Sheikh Jarrah, the roads are small and in need of repair, dotted with piles of rubble, shops are crowded together, making for rather cramped and filthy public spaces and for unsafe pedestrian walkways. We had to walk single-file much of the time, shouting to each other over the din of cars whizzing by. We felt completely safe from any political violence. First of all, there was none at least at that moment, and our host’s European good looks and crackerjack Arabic, correctly accented, gave us cover. We spoke only English to each other and to the few people with whom we interacted, to avoid any suspicion that we might be Jewish Israelis provocatively hanging around. I even went so far as to leave my Israeli-style walking boots in our apartment in Zichron Yaakov, choosing something else to wear on my feet, so as to avoid any overt association with Israeli popular culture. The main industry seems to be auto-repair shops, which have a high per capita ratio and which attract the attention of religious Jewish car-owners interested in inexpensive and reliable car maintenance. The local municipality has posted signs in Arabic and English wishing residents “Ramadan Kareem” – a sweet Ramadan. I asked our host what the local residents thought of that and he confirmed my impression that it reaches them as rather insincere. How about safer and better infrastructure, medical care and education for these Israeli citizens?

Our walk through the area gave a real life vignette of just how diminished civic infrastructure is here compared with west Jerusalem, just meters away. In Sheikh Jarrah, the roads are small and in need of repair, dotted with piles of rubble, shops are crowded together, making for rather cramped and filthy public spaces and for unsafe pedestrian walkways. We had to walk single-file much of the time, shouting to each other over the din of cars whizzing by. We felt completely safe from any political violence. First of all, there was none at least at that moment, and our host’s European good looks and crackerjack Arabic, correctly accented, gave us cover. We spoke only English to each other and to the few people with whom we interacted, to avoid any suspicion that we might be Jewish Israelis provocatively hanging around. I even went so far as to leave my Israeli-style walking boots in our apartment in Zichron Yaakov, choosing something else to wear on my feet, so as to avoid any overt association with Israeli popular culture. The main industry seems to be auto-repair shops, which have a high per capita ratio and which attract the attention of religious Jewish car-owners interested in inexpensive and reliable car maintenance. The local municipality has posted signs in Arabic and English wishing residents “Ramadan Kareem” – a sweet Ramadan. I asked our host what the local residents thought of that and he confirmed my impression that it reaches them as rather insincere. How about safer and better infrastructure, medical care and education for these Israeli citizens?

We returned to our host’s secure and beautiful apartment to drop off the dog, enjoy a feast of a snack and pick up our host’s spouse, back from a day of work in Tel Aviv. Then we headed out again, this time without the pup, to walk some adjacent areas populated by Israeli Arabs. We stopped in an extraordinary English-language book shop beautifully appointed and filled with all kinds of interesting titles and authors from Edward Said to Mahmoud Darwish to Madeleine Albright, z’l, and Tom Friedman. I met the bookshop owner who shared that he was committed to helping people learn about this complicated and painful situation. When he asked me what I did for a living I hesitated for a moment, then quickly realized there was no point in embellishing the truth, by saying, “I’m a teacher . . .” so I told him I am a rabbi and thanked him for all he was trying to do. He shook my hand and thanked me for coming.

Our hosts took us on a walk through the Muslim quarter of the old city, including a stop at the Austrian Hospice, a beautiful historic building with a spectacular rooftop view and some of the best strudel I’ve tasted. We continued on through the maze of stone streets passing many shopkeepers and residents, as well as IDF soldiers in small teams on security posts, and more microsettlements, these identified by Israeli flags. While I might be able to accept that the Jewish residents of these homes are themselves just expressing their national pride, it is impossible to deny the impression of hostility towards the Muslim residents which they convey by their presence. To my American Jewish eyes, it appears a completely inappropriate show of Jewish power in a place where Jewish wisdom is what is needed. Who is mighty? asks Pirkey Avot? The person who conquers their own self-serving impulse, according to our sages.

Our host wrangled a cab for us back to the apartment, stopping back in Sheikh Jarrah to pick up a take-out dinner from a very classy establishment, one filled with English-speaking patrons. Over dinner, we processed the afternoon and evening walks together, once again trying to dissect the Gordion knot of this place as so many others have done.

Jonathan and I made a late night visit to the pharmacy to retrieve my pain prescription – the Superpharm at Mamilla Mall was still open well past 10pm as were the other shops in this fancy shopping spot – and then to our hotel for the night. Outside the old city, back in west Jerusalem, we were again surrounded by the accoutrements of a modern, wealthy city. Not only well-paved streets and sidewalks bordered by professionally tended shrubbery, clear traffic symbols but many other signs of the good life, so clearly missing on the ‘other side’.

Monday morning was our long-awaited dual narrative tour with Mejdi tours, the company with which we had hoped to tour for our congregational trip, now postponed, and awaiting new dates. (Let’s please not let that go!) We found our guides outside the Jaffa Gate and joined with a group of 20 or so other tourists for a 4-hour tour of the old city, told from both a Jewish Israeli and a Palestinian perspective. The group had Jewish and Christian participants, from the States and from Europe. Our guides, Rabbi Josh and Hussam, took turns walking us through the Armenian, Muslim, Christian and Jewish quarters, with stops at several important places. Along the way R. Josh and Hussam graciously deferred to one another, sometimes politely disagreeing, about how to portray different parts of the history of this Ir Atiqa, ancient city. At different points along the way, we’d be in close proximity to different groups of visitors: Palestinian Israeli school children on a field trip, Asian tourists, observant Jewish and Muslim residents, and IDF soldiers. We visited a beautiful historic Armenian church courtyard, the church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Kotel HaMaaravi (Western Wall) and finally, Har HaBayit, the Temple Mount, which also home to the Dome of the Rock and Al Aqsa Mosque. With the exception of the final stop, the Temple Mount, these are all places I’ve seen several times, but felt I was seeing them anew through these dual lenses and the questions they provoked. What are the relationships between these ancient religions and what are their irreconcilable differences? It is hard but so important to remember that the antipathy between Jewish and Muslim communities today is rather new in the history of civilization. It is interesting to remember that while Judaism and Christianity are branches of the same original root (Biblical Judaism), they are more theologically opposed to one another than Judaism and Islam. Rabbi Josh reminded us that, according to Jewish tradition, Jews can pray in a mosque but not in a church. And at the end of the day, how do we stand strongly in our own tradition while treating the others with respect and even with reverence?

As I mentioned, the one place I had not been was the Temple Mount which is the site of the Dome of the Rock and Al Aqsa mosque, as well as the ancient Jewish Temple(s) before that. Just trying to craft this sentence is an example of how complicated this site is. Referred to as the “navel of the world” in both Jewish and Muslim tradition, it is beloved and revered by both traditions. Jews consider it the holiest place in Jewish history, the site of the Temple, which was destroyed and rebuilt and from which remains only the outer retaining wall, the Kotel. In Jewish tradition, we call it Har HaBayit, the Mountain Home, connoting a place of deep intimacy in all the ways that the word ‘home’ invokes. According to Jewish tradition, the Temple was built here on the spot that Abraham bound his son Isaac for sacrifice and from which God saved them both just in time. When Israel captured the Old City in the Six Day War, the exclamation, “Har HaBayit B’Yadenu!” – the Temple Mount is in our hands! – was a moment of profound Jewish communal healing and joy from an exile of nearly 2000 years. Tragically, that capture was also a turning point in the unfolding hostilities between Jews and Muslims here.

Muslims, arriving here several hundred years after Jews were exiled by the Romans, also cling to this spot as a centrally important one, knowing it as the site from which the prophet Muhammed ascended, and on which a spectacular structure has been built to house that stone of ascension. Perhaps because of this reverence, it has also been a minefield of explosive violence many times over. Access is tightly controlled, with Muslim visitors coming in through Muslim-controlled designated gates and non-Muslim visitors entering through one Israeli-controlled entryway, into which they must first pass through security detectors. As we waited on the long line to enter, a bar mitzvah entourage complete with a raucous Jewish musical ensemble and kind of chuppah (not for a wedding) made their way past us en route to the Kotel, singing loudly, an MC at the front with his own mic, encouraging us all to join in the celebration. Paradoxically, the bar mitzvah family were not particularly religiously observant, at least by their looks, and I had to wonder why they were dragging their poor son through this charade of a ritual. Again, I’m making no attempt to be non-biased here. I wish the boy well and his parents too, but aren’t there other meaningful and less-fraught places to gather for a religious celebration? (There are.)

A guard at the non-Muslim entry point to the Temple Mount determines which women are sufficiently covered and which are sent to the side to retrieve over-skirts and head cloths. It seemed inconsistent to me, but I’m no expert on religious headcovering. As we entered, we took in the signage explaining in Hebrew and English that it is not recommended for Jews to visit this site, which contains the Holy of Holies, into which only the high priest would enter, and therefore not appropriate for regular Jews. On the other hand, there were indeed observant Jewish visitors in the plaza of the Temple Mount, including one group accompanied by a rather bored-looking IDF soldier. People of all faiths meandered peacefully all around the plaza, taking photos and talking, with only Muslims allowed into the mosque. A pair of observant Muslim women accepted my offer to photograph them together in front of the golden domed Dome of the Rock and then invited me to be in their photograph.

While we waited for our group to reconvene to leave the Temple Mount, I chatted with Rabbi Josh, a modern Orthodox and most receptive teacher, about the challenges of Jewish triumphalism, the unfortunate outcome of the so-called doctrine of divine election, the idea that the Jews are the chosen people. As time has passed, redeeming Judaism from this problematic idea has become more and more important to me. I’ve found the Reconstructionist Jewish approach to liturgy to be an essential tool in this sacred task. How can we continue to say, as the traditional Alenu prayer does, “thank you God for not making us like the rest of humanity”, “for not placing us with the rest of the human families of the planet, nor our destiny like theirs.” Having a unique and special identity as a people is something we should embrace. Indeed Judaism (as a civilization) is unique and special. But the minute we define that uniqueness by what we don’t believe and by our distance from others, we squander its blessing by creating erroneous and spiritually damaging adversarial competition with other faith traditions. We don’t need all of that to express our uniqueness or even our special relationship with God. Redeeming ourselves, our tradition, from this unfortunate language allows us to embrace our unique identity while simultaneously creating the space for respecting others’ which is itself a key pillar of Jewish theology and spiritual life. This is particularly important to express clearly in our prayers which, unlike the Torah and Tanach, are aspirational, expressing ideas to which we aspire. I was not successful in convincing Rabbi Josh, open-minded as he is, and will step down off my soap-box for now, but my conviction remains and is strengthened by the experience of visiting these holy sites from which so much religious violence has erupted. We who are people of faith must pay attention to the power and danger of our words.

While we waited for our group to reconvene to leave the Temple Mount, I chatted with Rabbi Josh, a modern Orthodox and most receptive teacher, about the challenges of Jewish triumphalism, the unfortunate outcome of the so-called doctrine of divine election, the idea that the Jews are the chosen people. As time has passed, redeeming Judaism from this problematic idea has become more and more important to me. I’ve found the Reconstructionist Jewish approach to liturgy to be an essential tool in this sacred task. How can we continue to say, as the traditional Alenu prayer does, “thank you God for not making us like the rest of humanity”, “for not placing us with the rest of the human families of the planet, nor our destiny like theirs.” Having a unique and special identity as a people is something we should embrace. Indeed Judaism (as a civilization) is unique and special. But the minute we define that uniqueness by what we don’t believe and by our distance from others, we squander its blessing by creating erroneous and spiritually damaging adversarial competition with other faith traditions. We don’t need all of that to express our uniqueness or even our special relationship with God. Redeeming ourselves, our tradition, from this unfortunate language allows us to embrace our unique identity while simultaneously creating the space for respecting others’ which is itself a key pillar of Jewish theology and spiritual life. This is particularly important to express clearly in our prayers which, unlike the Torah and Tanach, are aspirational, expressing ideas to which we aspire. I was not successful in convincing Rabbi Josh, open-minded as he is, and will step down off my soap-box for now, but my conviction remains and is strengthened by the experience of visiting these holy sites from which so much religious violence has erupted. We who are people of faith must pay attention to the power and danger of our words.

Back to our tour. We finished in the Muslim quarter, following our guide Hussam back to the Jaffa gate, bidding everyone farewell, our heads spinning with so much intense history, imagery and rhetoric. Todah Rabbah and Shukran Katir . . . Thank you very much. And off we went in search of a late lunch and a place to rest before heading off to Tel Aviv for the night.

We took the train to Tel Aviv, arriving at HaHaganah station where we dropped off a care package for someone from Adat Shalom and started our walk to our hotel. I titled this blog submission, “both sides now” and thought of this phrase as we made this walk from the train to the hotel. What a difference a few train stops make. Here in this part of south Tel Aviv we walked through working class neighborhoods, past the old central bus station, and immediately noticed the change in skin color and language. In contrast to the mostly Ashkenazi, and therefore “white” appearing people with whom we’ve mostly interacted, we found dark-skinned people everywhere, along with signs of resource-scarcity in varying degrees. Buildings looked run-down, sometimes abandoned. Signs were written in Ethiopian and Russian even more than Hebrew and/or Arabic, and we felt an unconscious impulse to hold onto our bags just a bit more tightly. That is a commentary on our prejudices, not on the crime rate or the real security issues. It is also a commentary on the impossible intrasigence of racism, even within a religious group. The lower you go on the socioeconomic scale, the darker the color of people’s skin. I know that is not news to anyone, but seeing it in such stark vivid reality was startling. I was here in Israel in 1990 when the country was absorbing large waves of Russian and Ethiopian immigrants with great fanfare and was a little sad to see how they’ve been absorbed. To be fair, this is just one momentary snapshot, not the whole portrait, but I would love for Israel to rise to it’s special potential as a place that could break through some of those race-based stereotypes. (If the US can manage to put a Black woman on the Supreme Court – please let her be confirmed!! – Israel can surely do even more.)

After a morning walk to the beach in Tel Aviv, the main road lined with beautiful hotels, and the beach walk crowded with beautiful (mostly white) people whose lives afford them time for a morning run on the beach, we started our walk back uptown. Just days before, I had said to Jonathan, do you know if Noah Stern (who’s been here on a Masa internship) is still in the city? We guessed he was not, but quickly found out we were wrong as we passed him on the street! We grabbed hugs and agreed to meet up later in the day. We then found our way to Nachalat Binyamin, the twice-weekly crafts fair and for brunch with Adat Shalom friend Alysa Dortort. Alysa has finally begun her process of moving here after dreaming of it for many years and treated us to a delicious meal at one of her favorite places, which we also loved. After the initial decades of slim culinary pickings in Israel, especially during the official period known as austerity in the 1950’s, Israel has blossomed into a gourmet mecca. Only by walking a ton during our time here have we managed to stave off the pounds we should have gained by all the delicious food we’ve eaten, with portions for giants at every restaurant. We got a taste (!) of this on Monday evening, enjoying a late dinner in a newly burgeoning part of the city. Brunch with Alysa the next morning was indeed also a feast, made only better by the conversation about her life here in Tel Aviv. Moving halfway across the world is no joke, even to a place you love, and she’s managing it well, while staying in close touch with Aaron and Rebecca, still living in the States.

From there we walked through the craft fair and the nearby Shuk HaCarmel, Tel Aviv’s central market, once again overwhelmed by the abundance of just about anything you want to eat and/or buy. We were already full from brunch and heading to a tasting tour in the afternoon, so we mostly just looked and picked up a few basic items, just enjoying the experience. You don’t hear shop-owners at Montgomery Mall shouting over one another to attract customers, but here, the meek do not attract customers, nor do they inherit the profits they seek. Shouting and hocking are the most primal forms of advertising and still work well for the shop owners here. Just make sure you don’t stand too close!

We found our tasting tour guide, the lovely Penina, a young British archeology grad student at Hebrew University, who guides people like us as a side job. Our tour was all through the Levinsky Market, with Penina providing wonderful historical and cultural background for the whole area and for specific shops, several going back generations to the beginnings of Tel Aviv. The Market has become a hip stomping ground and home for a new flowering of culinary creativity. At one point, we wanted to sit down to rest a bit before the tour started and tried to ask the waitress, “may we order just a drink and no food for now?” She answered, “we actually don’t serve food, just drinks . . .” Fine! We’ll eat with Penina. Scrumptious: varieties of herring, marinated vegetables, gourmet custom-made fruit soda, stuffed grape leaves, olives, falafel, spices to taste, bourekas served with roasted egg and freshly ground tomato, Turkish coffee, the mostly heavenly babka and finally, halvah . . . sigh. Peace process? Political conflict? Water issues? Housing problems? Just take a break and eat a bite of fresh falafel. The problems will still be there when you’re done and you’ll be better fortified to work on them.

We did indeed catch up with Noah for a short afternoon break at the beach, the end of a beautiful spring day – finally, after a very long, cold winter – and caught up with his short-term and longer-term plans. His dad, our beloved friend Jonathan, z’l, would be happy to see this young man finding his own deep connection with Israel and trying to live here at least for now. Walking along the streets of the city, we too were again inspired by the irrepressible energy, creativity and ingenuity all around. Even with all of it’s socioeconomic and other problems, when you remember that Tel Aviv grew from literally nothing (okay, sand) just over 100 years ago and is now a thriving, cosmopolitan city with a vibrant culture, you can’t help but be inspired.

And finally, the most delightful end to this very full day, dinner with Mira Kux, near Tel Aviv University, where she is a student in Middle East studies and political science. As usual, Mira is continuing to blaze her own trail with such intelligence and passion, moving around the neighborhood with native comfort and ultimately guiding us to the train station to catch our train back to Binyanima, and then by cab back to our apartment in Zichron Yaakov, quiet, lovely, home. As we sat on the train, we saw the news of a third terrorist attack in two weeks, this time in B’nei B’rak, an ultra-Orthodox part of Tel Aviv, leaving five Jewish citizens dead. Before we left for this three-day trip, we were advised to avoid travelling to Jerusalem during Ramadan, which starts this coming Shabbat, since violence often increases with the arrival of this season. Sadly, past experience is instructive here again. While we’ve watched the coming Negev Summit with interest and hope, such progress often provokes negative reaction in other corners. So, from the comfort of our peaceful temporary home here, overlooking the Arab village of Furaidis, “Paradise”, we again offer prayers for peace and hope for the future, against all odds.

And finally, the most delightful end to this very full day, dinner with Mira Kux, near Tel Aviv University, where she is a student in Middle East studies and political science. As usual, Mira is continuing to blaze her own trail with such intelligence and passion, moving around the neighborhood with native comfort and ultimately guiding us to the train station to catch our train back to Binyanima, and then by cab back to our apartment in Zichron Yaakov, quiet, lovely, home. As we sat on the train, we saw the news of a third terrorist attack in two weeks, this time in B’nei B’rak, an ultra-Orthodox part of Tel Aviv, leaving five Jewish citizens dead. Before we left for this three-day trip, we were advised to avoid travelling to Jerusalem during Ramadan, which starts this coming Shabbat, since violence often increases with the arrival of this season. Sadly, past experience is instructive here again. While we’ve watched the coming Negev Summit with interest and hope, such progress often provokes negative reaction in other corners. So, from the comfort of our peaceful temporary home here, overlooking the Arab village of Furaidis, “Paradise”, we again offer prayers for peace and hope for the future, against all odds.

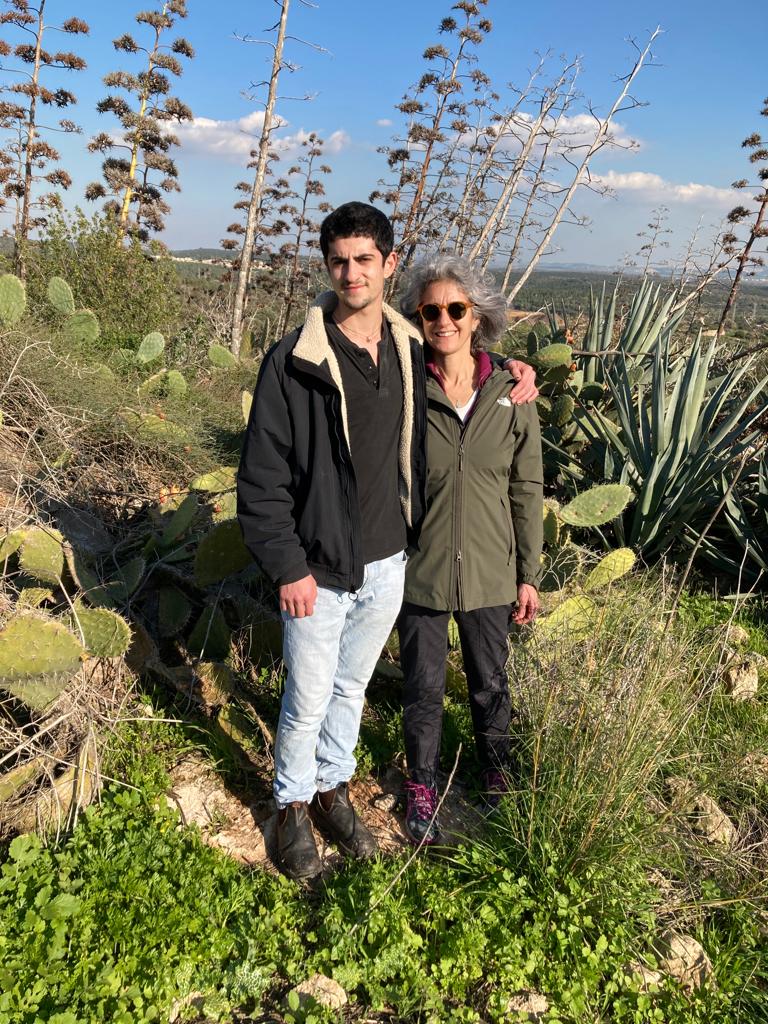

Do you hear that swoosh of air going by? That’s the sound of me (and Jonathan) exhaling fully after a week of holding our breath. Our son Koby was in Poland with his k’vutza (group) on a seminar as part of their program. Poland, you know, the one right next to Ukraine? After much discussion, and worrying by parents in the States, Canada and here, they did go ahead with the trip and it seems it was most profound. And, thankfully, safe. While visiting several important Holocaust sites, and learning about the Jewish resistance efforts during WWII, the group also participated in two service projects for Ukrainian refugees and got a first-hand look at the situation. They wrote their own group blog each day, shared their impressions and their feelings as they absorbed all of this intense suffering, from 80 years ago and from today. Koby received invaluable support from Adat Shalom to participate in this whole year-long program and has promised he’d share more with the community on his return.

Do you hear that swoosh of air going by? That’s the sound of me (and Jonathan) exhaling fully after a week of holding our breath. Our son Koby was in Poland with his k’vutza (group) on a seminar as part of their program. Poland, you know, the one right next to Ukraine? After much discussion, and worrying by parents in the States, Canada and here, they did go ahead with the trip and it seems it was most profound. And, thankfully, safe. While visiting several important Holocaust sites, and learning about the Jewish resistance efforts during WWII, the group also participated in two service projects for Ukrainian refugees and got a first-hand look at the situation. They wrote their own group blog each day, shared their impressions and their feelings as they absorbed all of this intense suffering, from 80 years ago and from today. Koby received invaluable support from Adat Shalom to participate in this whole year-long program and has promised he’d share more with the community on his return.

Meanwhile, back at this ranch . . .

It was great to see many of you this past Sunday on Zoom when we had some time to get to know Rabbi Elisha Wolfin, the spiritual leader of the Masorti (Israeli Conservative) community here in Zichron Yaakov. I asked Elisha to talk about the evolution of liberal Judaism in Israel, something that has not always been accepted here and still struggles for full legitimacy in this democratic Jewish state. Elisha reminded us that while the liberal movements, Reform and, later, Conservative Judaism spread westward from Germany, and have really flourished in North America, those liberal movements did not find much footing in Eastern Europe, nor in North African or Arab Jewish communities (especially Morocco, Tunisia, Iran, Iraq, Yemen) from where most immigrants to Palestine and modern Israel came. Especially in Eastern Europe, those Jews who followed a Zionist path to aliyah were either religious or secular. And, as is well known, the secular Jews were “religiously” secular, explicitly rejecting religion as Communist and Socialist ideologies tended to do. (My sister-in-law Ruthie’s kibbutz Ein Shemer had a banner of Josef Stalin hanging in the dining room in the early years of the kibbutz, removed only after it became clear that he wasn’t such a hero after all.) Conversely, religious Zionists were, and still are, schooled in traditional Jewish life, based on strict adherence to halacha. Hence the official, recognized form of Judaism in Israel is Orthodox. I note, somewhat sadly, that there is no liberal weekday minyan here, not on Zoom, not in person, so my talit sits folded up waiting for Shabbat; I really miss our Adat Shalom weekday minyan and look forward to rejoining it soon.

It is such a paradox that in an explicitly Jewish state, major forms of Jewish expression are seen as simply strange if not outright offensive. Wouldn’t this be the obvious place for all forms of Judaism to manifest? That was certainly the ideal of Zionist visionary Ahad Ha’am, who imagined a new State of Israel as the cultural and spiritual center of the worldwide Jewish community. But if change takes time, even a few generations, that change is apparent. While the government still does not recognize Masorti or Israeli Reform (forget about Reconstructionist and Renewal) clergy or communities, there is a growing interest in and desire for this more liberal approach to Jewish spiritual life as a generation of Israelis expresses their need for something other than black or white. As I noted during the call, I think of Ruth Calderon’s inaugural knesset speech, mentioned in an earlier blog, when she shared that, though she was raised in a strongly Zionist home, and has always felt committed to the ideals of the State of Israel, her “Tanach to Palmach” socialization and education left her feeling something was missing. So she started studying Talmud, picked up a Phd and founded a liberal yeshiva. Most Israelis don’t go that far, but more and more are participating in liberal Jewish spiritual life. On Purim morning, the congregation here joined with a liberal chavura visiting from nearby Pardes-Hanna for a shared megillah reading. Personally, I was so delighted with the two little girls arriving in Purim-inspired ballet tutu’s, (I miss the Miss Ellie community at Adat Shalom!) but certainly also appreciated the display of participation in this Jewish holiday from folks who are not officially “religious.”

That liberalization is even catching on among a small number of Orthodox Jewish Israelis. Last Shabbat morning, Jonathan and I joined a different local synagogue community which is “shivyoni”, meaning egalitarian. In this case, that label indicates that it is a traditional Orthodox group, in which there is a mechitza (physical divider/barrier between genders) during services, but which also welcomes men and women for equal participation and leadership. When counting heads for a minyan, they wait to be sure they have 10 men and 10 women, or at least they try. During the Torah service, a male gabbai stood on one side of the shulchan (reading table) and a female on the other side. The two took turns calling male and female honorees to the Torah for aliyot, evenly splitting the honors. Likewise, men and women shared the responsibility of leading the prayers. A woman led the Torah service, carried the Torah through the women’s side; the men got their turn when it was time to return the scroll to the ark. The mechitza was removed for the d’var Torah – given this week by a man – since there is no prohibition against mixed seating to hear a Torah teaching, only one during prayer. This coming Friday night, they will host a . . . female rabbi, a maharat, as they are called in liberal Orthodoxy, taking a cue from that movement in the US. It may be surprising to hear this, but I really enjoyed it as I have other such places I’ve visited. While I don’t follow the rationale of the separate seating myself, I like the idea of a place where a plurality of practitioners can participate together and where “thick” Judaism is accessible to a wider group. Needless to say, the question of how to welcome and integrate those who are gender neutral or gender non-conforming is one that still needs thought and a good solution.

And there’s another facet to this subject that’s been on my mind: the extent to which Jewish religion is often the only option for us Diaspora Jews who want to express our Jewish identity, while here in Israel, Jewish identity is so “thick” and generally integrated into everyday life, participation in Jewish spiritual life is not universally chosen by Jewish Israelis. Again, somewhat paradoxically, because Jewish traditions and ideas are practically part of the oxygen here, religious life in general is ironically a smaller piece of the portrait of Jewish society, when compared with the Diaspora. In an uncanny way, Jewish religious affiliation in the Diaspora is stronger because it has to be. As Elisha remarked on Sunday, most Israelis are appalled at the idea that they have to “join” a synagogue to be part of the Jewish community in North America. All of our marvelous shlichim, Erez DeGolan, Sahar Malka, Ayelet Levi and Idan Sharon, experienced Jewish religion personally for the first time at Adat Shalom! They gave us Israeli culture and we gave them Jewish religion, at least our version of it.

And there’s another facet to this subject that’s been on my mind: the extent to which Jewish religion is often the only option for us Diaspora Jews who want to express our Jewish identity, while here in Israel, Jewish identity is so “thick” and generally integrated into everyday life, participation in Jewish spiritual life is not universally chosen by Jewish Israelis. Again, somewhat paradoxically, because Jewish traditions and ideas are practically part of the oxygen here, religious life in general is ironically a smaller piece of the portrait of Jewish society, when compared with the Diaspora. In an uncanny way, Jewish religious affiliation in the Diaspora is stronger because it has to be. As Elisha remarked on Sunday, most Israelis are appalled at the idea that they have to “join” a synagogue to be part of the Jewish community in North America. All of our marvelous shlichim, Erez DeGolan, Sahar Malka, Ayelet Levi and Idan Sharon, experienced Jewish religion personally for the first time at Adat Shalom! They gave us Israeli culture and we gave them Jewish religion, at least our version of it.

Likewise, for North American Jews, trying to maintain a minority identity in a mostly welcoming and also mostly Christian-oriented culture has left us focused on Jewish religion more than any other expression of identity. And this isn’t always a recipe for success, individually or as a community. As one congregant wrote to me recently, “The chore of having to make “religion” the sole (or main) expression of our Jewish-ness is daunting, but in the diaspora, that’s what we have to do.” In his definition of Judaism as “an evolving religious civilization” Mordecai Kaplan was onto something. Religion is important to Jewish identity, maybe even at the core of it, but religion alone is not a satisfying expression of the fullness of that identity. We need to know our history, our literature, our music, our art and architecture, our sports and, for sure, our food. Israeli society supplies the ground and the fertilizer for all of that Jewish civilization to grow and thrive. It ain’t always pretty; as Elisha commented, Israelis (maybe Jews in general?) need to argue, to speak their minds candidly. On the other hand, you never have to wonder what they’re thinking. Their thoughts are rarely smoothed over with the polite concealments we have in American culture, for better or worse.

The meeting point between Jewish religion and Jewish identity is porous and changeable throughout our lives, of course. We Diaspora Jews need Israel to push us to see outside the walls of religious practice and to remember that Jewish identity is bigger than the synagogue. At the same time, Diaspora liberal Judaism is slowly catching on here, modified to fit an Israeli culture, and is important in helping the dream of the Zionist founders to come to life.

The “shivyoni” egalitarian Orthodox community recited Psalm 130 on Shabbat morning in solidarity with the victims of the war in Ukraine, a most fitting prayer to offer from the Tanach:

Out of the depths, I call to you ETERNAL ONE. My God, hear my voice, let Your ears be attentive to my plea for mercy.

*Please join me this coming Sunday, March 20, 9:30am-10:30am (note the earlier beginning time!) for a Zoom conversation with Rabbi Elisha Wolfin, a Masorti (Conservative, i.e. liberal Jewish) spiritual leader.*

For You, God, are Most High

For You, God, are Most High

Surpassing all others

Those who love God, hate evil

God is a guardian of the souls for those devoted followers

God will save them from the grasp of evildoers

-Psalm 98

Like all of you, we are watching the unfolding Russian war against Ukraine with horror and anger. The contrast between our idyllic sabbatical lifestyle and the news is almost too much to bear. Who wants to visit ancient sites, practice for the megillah reading or even talk about the political challenges here when such a crisis is growing with each passing minute. On the other hand, what good does it do anyone in Ukraine (or in the neighboring countries now absorbing the more than 2 million refugees who’ve fled the war) to sit in my apartment and wring my hands? As I often do, I’ve found some solace in prayer, in the opportunity to express myself in the words of our siddur. Sometimes the liturgy just says it best. So, when it was my turn to lead Kabbalat Shabbat for the community here last Friday, I turned to these verses from Psalm 98, shown above. These lines have always stood out for me. They seem a rather sinister departure from the more common psalm verses we chant on Friday night, many of which highlight the renewal of creation, and the joy in resting from it. But, as the prophet Isaiah surely knew – God is the “creator of malice” – life includes these dark times as well, and so must our prayers. Searching for a way to highlight these words during the service, I worked out a way to sing them to the melody of the Ukrainian national anthem. I found myself practically shouting the last phrase, “God will save [the devoted ones] from the grasp of evildoers” wishing that my prayer could somehow help. Perhaps the only one it will help is myself, but that is better than nothing.

And just to keep it real, I can add that while I am more than capable of expressing myself in Hebrew, I found myself too shy in the moment to explain the melody and why I chose it for these words, so, other than Jonathan, I’m not even sure if anyone got it! Oh well, Shabbat will come again this week.

Tomorrow night is Purim. We have little bits of costuming to wear to the Megillah reading tomorrow night and Thursday morning. I’m going as a wood nymph, something I can wear that doesn’t interfere with my reading glasses, and Jonathan has a neon cowboy hat. I will delight in chanting the verses of chapter 8, my assignment, which includes Esther’s moment of truth and then the famous climax when Mordecai rides out in the king’s robes and “all the city of Shushan rejoiced and was glad”. And everyone’s favorite, “for the Jews there was light and joy and gladness and dear connection”, so beloved a verse it was conscripted into the Havdalah service. But I bet it is going to feel kind of macabre doing all this celebrating right now. Our Purim celebrations will be as prayers for peace and justice, for a restoration of safety and security for refugees and victims. I’m holding onto a teaching from a colleague in NY who highlighted the tiny phrase from the Megillah, “et zot”, meaning “this moment”, as in, “this is the time to act”, as Mordecai tells Esther. May our leaders have the courage and wisdom of Queen Esther to act to bring a safe and complete end to this madness.

The weather has been uncharacteristically cold and windy the last few days, the sky a little darker. Our local Purim celebrations, originally planned for outdoors, at a cafe and then in Ramat HaNadiv, the local memorial park, have now been moved indoors. The stores are selling costumes and we saw Harry Potter running home from school near the synagogue just today, but the chill in the air is also noticeable. Maybe that’s fitting for a year when Purim can just as well be a little muted. Instead, let’s turn our Purim attention to the custom of matanot la’evyonim, gifts to the poor. We may not be able to stop the Russian army, but we can strengthen the hands of those trying to protect innocent victims caught in this despicable, unjust war through no fault of their own. Pick your favorite place and give: local Federation emergency fund, HIAS, UNICEF, IRC, JDC, among many other worthy groups. And may Puti . . . oops, I mean Haman’s name be wiped out.

By now, if you’re reading this, you’ve likely also seen the announcement about my plans to transition to a new position this coming fall. So many of you have sent so many good wishes – I’m extremely grateful for all your kind words. I’m trying to respond individually, but may not have gotten all caught up yet. And we still have more than 6 months in our current configuration, so, you’re not rid of me yet.

By now, if you’re reading this, you’ve likely also seen the announcement about my plans to transition to a new position this coming fall. So many of you have sent so many good wishes – I’m extremely grateful for all your kind words. I’m trying to respond individually, but may not have gotten all caught up yet. And we still have more than 6 months in our current configuration, so, you’re not rid of me yet.

Back to our regularly scheduled program . . .

Being the second youngest in his original nuclear family of 6 kids, Jonathan has a large web of nieces, nephews and now great-nieces and nephews. His eldest nephew was born when Jonathan himself was a young teen. I say this to explain that, yes, we are entirely too young to be called grand uncle Jonathan and grand aunt Rachel, yet, somewhat alarmingly, this is what we are!

Last week, we caught up with one of the elder nieces and her family, enjoying a visit we had previously postponed when one of her daughters tested positive for omicron. We were delighted to bring a Thai dinner by special request from our grand-niece, from the local mall – owned by the kibbutz where they and Jonathan’s sister live – and join this family of 5 on a Thursday night, which is when the weekend begins here. Our niece Yasmin, mentioned in an earlier post, and her husband Atar, are parents of three wonderful kids. Yasmin is a local high school Tanach (Hebrew Bible) teacher and Atar is an artist and art teacher, traveling to Tel Aviv several days a week, teaching all different kinds of media, while he himself is a successful painter. Their son Maayan Zoomed into our Kitah Zayin at Adat Shalom last year when we were learning about modern Israel, acting as my own personal show and tell. Their daughter Romi, who shares my love of Pad Thai, met us in the kibbutz parking lot and walked us back to their home, her warm grace belying her pre-adolescent age, and we were quickly scooped into their busy home to gather around their family table. As the family chatted about all kinds of things – Atar is helping to build a new playground for their youngest daughter, Gali’s, kindergarten class – I thought about some differences between typical Israeli homes and typical American homes, first and foremost the difference in size and the perception of how much space we “need”. This awareness of personal space – physical and moral – is one of the principles of Jewish ethics, in particular, the practice of mussar, which says, “no more than my space and no less than my place.

Yasmin’s kibbutz home is comfortable by Israeli standards, with room for three kids to spin around the shared living space, and a kitchen big enough to prepare meals for an active family. Their dining table is intimate by American standards, but, to tell the truth, it was more than big enough for us and made it easy to share dishes and conversation. Emphasis on connection and relationship, not on personal space. (And, Daisy, their puppy, wanted in on the action too.) Perhaps this is just the result of geographical and economic reality – Israel is a tiny country and, until recently, not very wealthy – but it seems a good lesson for us in the west, accustomed to spreading out and taking up whatever space there is. Do we really need all of our space? Another family visit pushed the question further.

On Shabbat we finally made it to visit our youngest Israeli niece Ayala, her husband Ori, their toddler and their newborn in Kiryat Ono, on the outskirts of Tel Aviv. I had not seen this lovely pair since before their wedding, when I was last here in 2016, and they were just dating. Now they are a family of four and doing an outstanding job of juggling being professionals (he, a career officer in the IDF ), full-time students (she, now working on a 2nd bachelor’s degree) and parenting an adorable two-and-a-half year old and a one-month old. It seems I will not have grandchildren of my own any time soon – again, far too young – but being with these little ones is a taste of the deliciousness I anticipate (someday!) The toddler was shy for about 5 minutes, then eager to share his toys and to ask, “why?” about everything, right on cue developmentally. The newborn slept peacefully while her parents served lunch, politely waiting until we were all done eating before tactfully announcing the end of her nap. The tired parents somehow remained good humored, patient and firm with their toddler, while they chatted us up, mostly in English, not their native tongue, and managed all of this activity.

Among the whole extended family, this couple are the only ones who’ve adopted a traditional Jewish lifestyle, what I would categorize as “Dati Le’umi” – which is basically modern Orthodox. They are completely comfortable in the modern world and also observe Shabbat, kashrut and other Jewish laws with precision and clarity. So, for instance, not only could we not bring homemade food from our kitchen here, which is not kosher, we also could not bring hechshered items from a store since they’d be transported in a car on Shabbat. I share this without an ounce of judgment or disparagement, more out of interest and respect. And, yes, it felt terrible to show up at the home of new parents and have them feed us rather than the other way around. And not just some little nibble, but a full homemade Shabbat lunch, with “Iraqi” cholent, the delicious stew cooked hot and slow (from chaud and lent in French), often started on Friday morning so it will be ready for Shabbat lunch. But we will get them back another time soon.

As we entered Kiryat Ono, with its many apartment buildings and otherwise low-key atmosphere – this is not the fast-paced, cosmopolitan center of Tel Aviv, but more of a bedroom community – we were immediately aware, again, of the difference between Israelis and Americans in how much space we feel we need to live. Ayala and Ori live in a modest apartment, smaller than the one we’re renting in Zichron Yaakov, which is . . . small, but, we’re surprised to discover that it is more than sufficient for us. Our young niece is living with her young family in a smaller space, but it seems more than fine. Heck, if you can have homemade cholent and fresh beet salad for lunch, who cares what size the table is? As long as there is room for your bowl and your tush? And, you have your brilliant and adorable young grand-nephew sitting nearby to explain all the ingredients in the salad – in perfect Hebrew mind you! – what’s not to like? All I’m saying is, our 2700 sq ft home in Bethesda now seems absurdly large for two people who’s young adult kids drop by now and then. Wicca Davidson, let’s talk.

As we entered Kiryat Ono, with its many apartment buildings and otherwise low-key atmosphere – this is not the fast-paced, cosmopolitan center of Tel Aviv, but more of a bedroom community – we were immediately aware, again, of the difference between Israelis and Americans in how much space we feel we need to live. Ayala and Ori live in a modest apartment, smaller than the one we’re renting in Zichron Yaakov, which is . . . small, but, we’re surprised to discover that it is more than sufficient for us. Our young niece is living with her young family in a smaller space, but it seems more than fine. Heck, if you can have homemade cholent and fresh beet salad for lunch, who cares what size the table is? As long as there is room for your bowl and your tush? And, you have your brilliant and adorable young grand-nephew sitting nearby to explain all the ingredients in the salad – in perfect Hebrew mind you! – what’s not to like? All I’m saying is, our 2700 sq ft home in Bethesda now seems absurdly large for two people who’s young adult kids drop by now and then. Wicca Davidson, let’s talk.

In between the nieces, we scored a visit with Micha and Rachel Balf of nearby Kibbutz Maagan Michael. Special shoutout to Rabbi Fred from Micha who was a shaliach in Boston when young Fred Dobb was an undergrad at Brandeis, and again in Washington around 2006-7 when Fred was already “a big rabbi at a big shul in Washington DC!”. Rachel is one of the regular Torah readers at Kehilat Veahavta and we quickly realized the connections. Micha and Rachel welcomed us into the kibbutz for a Friday morning brunch in the chadar ochel (kibbutz dining room), then handed us bikes and took us on a tour of this beautiful place, where they’ve lived since the 1980’s. They spoke with understandable pride about the success of the kibbutz, one of the few that still operates as a collective. Micha’s career has been in education, first as a teacher of civics and literature, and later as principal of the regional high school. Rachel is a social worker. Both of them are especially enjoying their current role as grandparents, whose grandchildren live on the kibbutz as well. Our tour of the kibbutz ended with a stop at their home, also lovely, also right-sized. If I saw it in a real estate ad, I’d dismiss it as insufficient in size, but entering the space it seems more than ample and a wonderful place to live.

Earlier this week, I stopped at my favorite local coffee shop, right near our apartment. They already know me by now and start pulling the decaf coffee grounds down from the shelf (apparently, no one else orders decaf) and the soy milk from the fridge. The usual? Yes, the usual, I answered, squeezing past another customer to the counter credit card reader to pay my bill. It is barely enough room to maneuver, but then again, it was fine. And, finding a seat at a small table outside where the sidewalk disappears into the street and I can smell the citrus from the fruit market across the narrow road, I settled in to enjoy my steaming cuppa decaf. New customers squeezed past me, the cafe owner edged his way through with a tray full of drinks, and it was all rather cozy. But somehow, not crowded. Right-sized.

And finally, yesterday, with a few hours of freedom before meetings and other commitments, we made the drive back to Akko, the ancient and modern city I mentioned in my blog about cooking. I wanted to show Jonathan the remarkable site of our cooking class and around the old city, which is home to Jews and Arabs living in close proximity, another locale of mostly peaceful coexistence which erupted in violence last spring, but which has now resumed its peaceful rhythms, at least for the moment. While we took in several old and ancient sites – Napoleon was here, R. Moshe Chayim Luzzato was here, the Crusaders were here, the Romans were here, several Mishnaic sages were here, some say even D’vorah the judge was buried here – we also learned the local art of close navigation around others walking the same very narrow streets. Often, you have to turn sideways to fit two people passing one another in a kind of pedestrian dance, before emerging into a wider plaza where a motorcycle might be zooming by. I guess it could get claustrophobic, but people seem fine with it.

And finally, yesterday, with a few hours of freedom before meetings and other commitments, we made the drive back to Akko, the ancient and modern city I mentioned in my blog about cooking. I wanted to show Jonathan the remarkable site of our cooking class and around the old city, which is home to Jews and Arabs living in close proximity, another locale of mostly peaceful coexistence which erupted in violence last spring, but which has now resumed its peaceful rhythms, at least for the moment. While we took in several old and ancient sites – Napoleon was here, R. Moshe Chayim Luzzato was here, the Crusaders were here, the Romans were here, several Mishnaic sages were here, some say even D’vorah the judge was buried here – we also learned the local art of close navigation around others walking the same very narrow streets. Often, you have to turn sideways to fit two people passing one another in a kind of pedestrian dance, before emerging into a wider plaza where a motorcycle might be zooming by. I guess it could get claustrophobic, but people seem fine with it.

We adjust to the space we have and, in doing so, find out that we may not need so much. In an earlier visit with Jeremy Benstein, he remarked about why so many young Israelis go abroad after their army service. They feel boxed-in here – there’s not much room, and not many places to go inside the national borders. This is very different from the States where a traveler can stretch their “legs” easily, even within the same state. So, off they go to visit India, Thailand, South and North America, bringing back new cultural ingredients to refresh what’s already here, and then, usually, settle into the available physical space with expanded minds and hearts. Apparently, the founder of mussar, R. Israel Salanter, said, “the greatest distance is between the human mind and the human heart.” I assume he meant that the task of spiritual practice is to bring the two together, to integrate our cognitive and emotive intelligence into one consciousness, like the Buddhist idea of bringing the jewel (the mind) into the lotus (the heart). And at the same time, the spaciousness in our consciousness, to dream of what is possible in the world: peace, plenty for all, health and safety, should never be limited.

At the end of the Book of Exodus and again in the beginning of the Book of Numbers, the Torah goes to great lengths to describe the construction and ritual use of the original menorah, the seven-branch lamp which, according to the Torah text, stood in the mishkan, and which we know existed for sure in Temple times. It is depicted on the Arch of Titus in a frieze showing the spoils of war which the Romans extracted from Jerusalem after the destruction of the 2nd Temple. While we often envision the modern Israeli flag as the most obvious visual of Israeli society, the menorah is the official state symbol. When the modern State of Israel was established in 1948, the menorah was a potent sign of Jewish renewal and reclamation and the end of the diaspora which began with that Roman destruction in the first century CE. But it has even more importance in the foundation of Judaism as a religious civilization.

At the end of the Book of Exodus and again in the beginning of the Book of Numbers, the Torah goes to great lengths to describe the construction and ritual use of the original menorah, the seven-branch lamp which, according to the Torah text, stood in the mishkan, and which we know existed for sure in Temple times. It is depicted on the Arch of Titus in a frieze showing the spoils of war which the Romans extracted from Jerusalem after the destruction of the 2nd Temple. While we often envision the modern Israeli flag as the most obvious visual of Israeli society, the menorah is the official state symbol. When the modern State of Israel was established in 1948, the menorah was a potent sign of Jewish renewal and reclamation and the end of the diaspora which began with that Roman destruction in the first century CE. But it has even more importance in the foundation of Judaism as a religious civilization.

As we’ve studied in past Torah discussions, there are multiple rabbinic commentaries on the description of the menorah in the Torah which point to it as a reference to the Garden of Eden. R. Shai Held and others have remarked on this connection in recent times, highlighting the many details rendered in botanical images, which harken back to the Tree of Life in the Garden. From Exodus 37:18-20:

Six branches issued from [the menorah’s] sides: three branches from one side of the lampstand, and three branches from the other side of the lampstand.There were three cups shaped like almond-blossoms, each with calyx and petals, on one branch; and there were three cups shaped like almond-blossoms, each with calyx and petals, on the next branch; so for all six branches issuing from the lampstand. On the lampstand itself there were four cups shaped like almond-blossoms, each with calyx and petals . . .

All of this was on my mind as I approached my Torah reading for this past Shabbat, so much so that I asked R. Elisha if I could say a few words before I began the reading. So, not only was I sweating to learn the 13 verses of Torah, all in this highly technical language in which one calyx starts to sound like another, but now I was also offering to speak about it all, in Hebrew. A glutton for punishment, for sure. But the Garden beckoned, so I put my head down and tried my best. Who knows what the authors of the Torah text were thinking about in so painstakingly describing the construction of this and other parts of the communal spiritual space. But the rabbinic creativity in connecting it to the Garden of Eden is inspiring. In my short d’var Torah – a “d’vareleh” I would call it – I said:

Seen through the lens of its symbolic meaning, the menorah calls up all the drama of the Garden, of the discovery of our human mortality and vulnerability, and also reminds us of a place of primordial beauty and generativity. And, since it became the custom for synagogues throughout Jewish history to include a menorah in memory of this original one, we too invoke that image of the Garden, so that whatever the simplicity or grandeur of our communal space, we have a little window on our first human experiences.

A few weeks ago, we took a walk with our brother in law through the Langa Grove [a historic park in Zichron Yaakov]. He reminded us to pay attention to the new almond blossoms, the first trees to bloom and to announce the arrival of spring. And here we are on Shabbat Shekalim, the first of the special Shabbatot which lead to Pesach. Let’s read these verses which point us to the image of the Garden and also help us to raise up our faith in the coming season of health and liberty, to see the decline of the pandemic and the festival of Pesach.

Amen and may it be so for us and for all dwellers of the earth, especially those innocent citizens of Ukraine caught in the crossfire of a maniacal and unjust invasion.

Here’s what else I learned: don’t write your d’var in English and then try to translate it into Hebrew, even if that means your final product will have to be a bit simpler in phrasing and linguistic substance. In fact, that is what I tried to do. I leaned heavily on my sister-in-law Ruthie for her precise eye and tireless devotion to editing – she has more patience than most saints – and went above and beyond the basic request for help. So much so that I had to practice the Hebrew version to be sure I understood it myself. I did manage to do so and delivered my first (and perhaps only!) drash in modern Hebrew. Phew. And yet I live to tell the tale, and even made it through the tough Torah reading with good success. The cherry on top was that the honoree for this reading was R. Elisha’s mother, celebrating her 80th birthday. I should only look and sound as good as she does, even now

your final product will have to be a bit simpler in phrasing and linguistic substance. In fact, that is what I tried to do. I leaned heavily on my sister-in-law Ruthie for her precise eye and tireless devotion to editing – she has more patience than most saints – and went above and beyond the basic request for help. So much so that I had to practice the Hebrew version to be sure I understood it myself. I did manage to do so and delivered my first (and perhaps only!) drash in modern Hebrew. Phew. And yet I live to tell the tale, and even made it through the tough Torah reading with good success. The cherry on top was that the honoree for this reading was R. Elisha’s mother, celebrating her 80th birthday. I should only look and sound as good as she does, even now

It happened to be my birthday as well. So we ended the day with a family celebration with Koby, cousin Josh and his amazing sons, both living here as well, one an officer in the IDF (just received the Presidential Commendation for outstanding service, just to kvell a little) and the other a precocious (and somewhat frustrated) music teacher and high school guidance counselor. Listening to the next generation talk about their perspectives, their dreams, their questions was wonderful for us. Among the threads of conversation, we chatted briefly about the war in Ukraine and the Israeli response to it. While there were many expressions of concern and prayer offered during the Shabbat service, the official government response is ambivalent: the foreign minister condemned it and the prime minister is attempting a stance of neutrality. And now Bennett seems to have a potential role in brokering a cease-fire. Whatever official statements made by various leaders, my prayers are with the citizens, young and old, bearing the brunt of this attack as sacrificial lambs while the world watches. May it end quickly.

And we carry on – what choice do we have? Yesterday, we made a trip to another less well-known historic site, Tel Dor, an important port city stretching back to Phoenician times (approx. 1500-300BCE), with updates from Roman and Crusader periods as well. Yet another spot where every stone has a story to tell and has been carefully excavated and preserved under Israeli rule. And just to take the shine off a bit, while we wandered around the ruins and took in the beauty of the Mediterranean waves gently splashing over them, we eavesdropped on a tour guide doing his best to present some of the extraordinary history here to a group of somewhat unruly middle school students, stopping several times to try to bring them to order, or at least to civility. Youth is wasted on the young.

We continued on to the Mizgaga Museum nearby at Kibbutz Nachsholim, housed in a glassworks factory which operated for all of maybe 3 years trying to produce bottles for the wine in the nearby vineyards, part of the Rothschild family vision, until it was finally determined that the glass bottling operation was not really viable. More recently, a museum has been created there to showcase a spectacular collection of archeological artifacts from the area, dating back to Phoenician times. The ingenuity of ancient peoples – no internet, no youtube instructions, no fancy tools or 3-D printing – is astounding. As we walked through the exhibit, I kept wondering why all this history was of no interest to the Ottoman Arab residents who populated this area before Jews started arriving here in the late 19th and early 20th century. Or maybe it has been of interest, but we don’t know about it. Our guide explained that they were likely busy just trying to earn a living, like we all are. (He added that relations between Arabs and Jews in this area in earlier times were often very good, mentioning that the local Sheik had hoped to marry his daughter to Meir Dizengoff’s son – it didn’t happen but is maybe one small example of warm relations that we don’t often hear.) Fair enough. Israelis have certainly also been busy with day to day needs. But the endless interest in history – not just Jewish but of all periods – which inspires all this archeological industry and its careful presentation to the public must be based on a primal love for this land. May that love also inspire a commitment to peace and justice.

At the end of the museum, a poem by the great Israeli poet Yehudah Amichai is posted on the wall:

Instructions for the Waitress

Don’t clear the plates and glasses

From the table. Don’t rub

The stain out from the tablecloth! It’s good for me to know

There lived others in this world before me.

I buy shoes that were once on another man’s feet

My friend has thoughts of his own

My love’s a married woman

My night’s used up with dreams

Drops of rain are painted on my window

The margins of my books are filled with others’ comments.

On the blueprints of the house I went to live in

The architect has sketched in strangers at the door

On my bed’s a pillow, with

The indentation of a head, no longer there.

So please don’t clear

The table,

It’s good for me to know

There lived others in this world before me.

____________________________________________________________

** Mazal tov to Gili and the whole Sherlinder-Morse-Dobb family on this upcoming simcha on Shabbat! Jonathan and I are cheering you on from over here and are with you in spirit.**

In our family, everyone says my tombstone will read “let me just make a quick salad”, since I seem to need to do this at many if not most family meals. Indeed, I really like having fresh, uncooked vegetables on the table; I also enjoy having something healthy that I can eat with abandon with little concern over the calories. I love the combination of vibrant colors, and the varied textures in your mouth as you crunch your way through cucumbers, peppers, varieties of lettuces and other ingredients. While I was raised with this kind of food aesthetic as a kid, my real love of salad was ignited by my first visit to Israel in 1990. At the time, I was assigned to the ‘cold self service’ tray as part of my kitchen duty at Kibbutz Ein HaShofet (a large, Hashomer Hatza’ir kibbutz, named in honor of “the judge” Louis Brandeis.) There, I learned the value of a truly beautiful scallion – “we eat this for the green!” the manager would shout at us if we served wilted onions – and the delight of chopping and mixing vegetables precisely.